Updates on Treating Congestive Heart Failure, Part 2: Guidelines for Diagnosing Congestive Heart Failure in Dogs with Chronic Degenerative Valvular Disease

Dr. Simon Dennis

BVetMed, MVM, DECVIM (Cardiology)

This article will describe the ACVIM staging system for chronic degenerative valvular disease in dogs and how to diagnose each stage, with emphasis on left-sided congestive heart failure. It will set the scene for subsequent articles that will discuss the management of disease in each stage.

Chronic degenerative valvular disease (myxomatous mitral valve disease, endocardiosis):

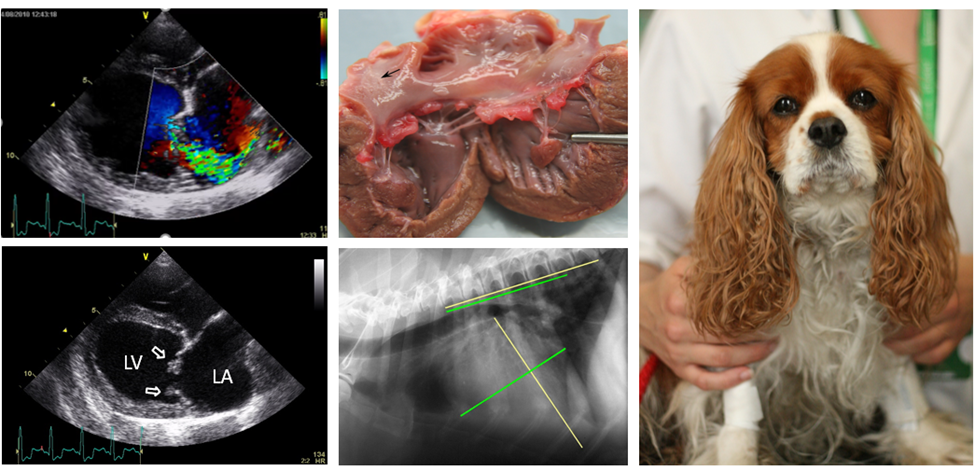

Chronic degenerative valvular disease is the most common heart disease of dogs, accounting for approximately 75% of canine heart diseases. The disease is referred to by many other names, such as myxomatous mitral valve disease and endocardiosis. Each name has strengths and weakness in describing the condition. For the purposes of this article, I will refer to it as chronic degenerative valvular disease. While the exact cause is not known, the higher prevalence of this condition among certain breeds and the increased incidence with age indicate that the most important factors in disease causation are genetics and time (1). As far as we know, infections, obesity and diet do not appear to play a role in disease development. The condition can range from mild, asymptomatic disease that is stable for several years, to rapidly progressive disease with heart enlargement, congestive heart failure, pulmonary hypertension, arrhythmias, and sudden death. Of all the biological variables that influence disease severity and progression, the most important determinant is the severity of mitral regurgitation. This is most accurately quantified by echocardiography.

The ACVIM Staging System:

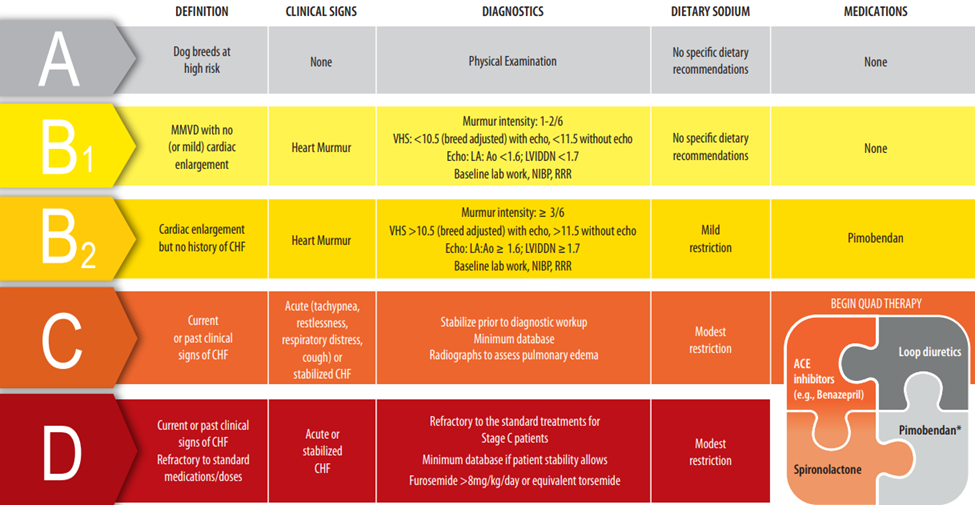

There are multiple systems for quantifying severity of chronic degenerative valvular disease, each based on different methodology. The system advocated by most veterinary cardiologists is one developed by the ACVIM specialty of cardiology consensus panel, which was first published in 2009 (2) and updated in 2019 (3). The system is adapted from a classification system devised by the ACC and AHA for use in humans with heart disease and heart failure (4). The ACVIM system groups disease into stages, termed A, B1, B2, C and D, with each stage related to the presence and severity of mitral regurgitation. The determinants of each stage are presence of mitral regurgitation (A to B), secondary heart enlargement (B1 to B2), presence of congestive heart failure (B to C) and severity of congestive heart failure (C to D).

Stage A:

Dogs in this stage do not have identifiable structural heart disease. They are defined as dogs that have a known high risk for developing chronic degenerative valvular disease. Examples include all older, small-breed dogs, and adult dogs of breeds with a known predisposition for the disease (e.g. Cavalier King Charles Spaniels). Since dogs in stage A do not have heart disease, this stage is rarely used in any clinical description of the disease, and it has no relevance for treatment. The utility of this stage is for the identification of dogs that should be screened for future development of chronic degenerative valvular disease.

Recommendations for screening high-risk dogs include frequent cardiac auscultations to detect a systolic click or left-sided heart murmur, and ensuring that auscultations occur in the best possible environment to detect abnormal heart sounds (e.g. in a quiet room). Some owners opt for screening echocardiograms. While this is not inappropriate, the value of an echocardiogram in a dog without a heart murmur is debatable unless the owner intends to use the dog for breeding.

Since stage A does not describe dogs with actual heart disease, this stage will not be discussed further in subsequent articles.

Stage B:

Dogs in this stage have identifiable structural abnormalities of chronic degenerative valvular disease (i.e. characteristic structural valve abnormalities, mitral regurgitation), but have never developed clinical signs as a result of heart failure. Definitive diagnosis of stage B disease requires echocardiography. Most dogs with stage B disease have a heart murmur of mitral regurgitation and are asymptomatic for their heart disease. This stage is divided into 2 clinically meaningful substages:

Stage B1 describes stage B disease with no, or minimal, evidence of cardiac remodeling (left atrial and left ventricular enlargement) in response to their mitral regurgitation. Dogs with stage B1 disease have not been shown to benefit from any treatment.

Stage B2 describes stage B disease with evidence of cardiac remodeling (left atrial and left ventricular enlargement) in response to their mitral regurgitation. These dogs typically have more severe mitral regurgitation than those with stage B1 disease.

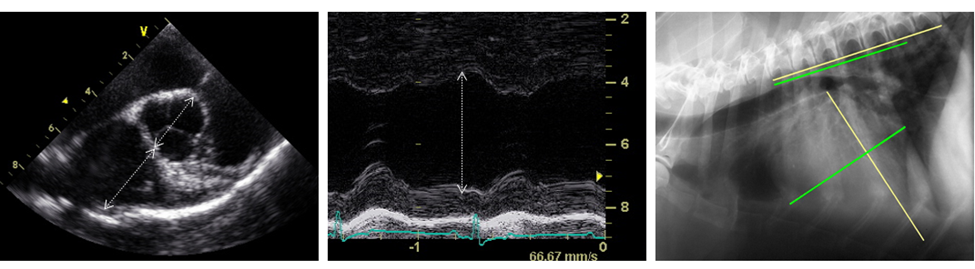

The specific auscultation, radiographic and echocardiographic criteria that distinguish stage B1 and stage B2 disease are as follows (3):

- Left-sided heart murmur of intensity ≥3/6.

- Echocardiographic left atrial to aortic ratio in the right-sided short axis view in early diastole (LA: Ao) ≥1.6.

- Echocardiographic left ventricular internal diameter in diastole, normalized for body weight (LVIDDN) ≥1.7.

- Breed-adjusted radiographic vertebral heart size (VHS) >10.5.

While all 4 criteria should be met for a diagnosis of stage B2 disease, ACVIM consensus panel elaborate further: “Of these criteria, echocardiographic evidence of left atrial and ventricular enlargement meeting or exceeding these criteria is considered to be the most reliable way to identify dogs expected to benefit from treatment” (3). This recommendation derives from the finding that a VHS >10.5 correctly identifies only two-thirds of dogs that meet the echocardiographic criteria of stage B2 disease (5,6). As a veterinary cardiologist, I am also comfortable to use only cardiac auscultation and echocardiography to diagnose stage B2 disease. However, since echocardiography with a board-certified veterinary cardiologist is not available to most patients in general practice, there are useful radiographic criteria that can be used, in combination with a left-sided heart murmur of intensity ≥3/6. Published studies have shown that a vertebral heart size of >11.7 (6) and a vertebral left atrial size >3.0 (7) correctly identify >97% of dogs with stage B2 disease.

The rationale for dividing stage B disease into substages B1 and B2 is that there is a difference in management and prognosis between each substage. Most dogs with stage B1 disease will take several years for their heart disease to progress to clinical disease, congestive heart failure, and death. Some dogs have a normal or close to normal life expectancy. However, for dogs with stage B2 disease, it has been shown that approximately 50% progress to congestive heart failure within 2 to 2½ years (8). Similarly, while no treatment has been shown to slow progression of stage B1 disease, there are studies showing benefits of certain treatments for stage B2 disease.

Management of dogs in stage B disease will be discussed in the next article in this blog.

Stage C:

Dogs in this stage have current or past clinical signs of heart failure. Affected dogs are typically symptomatic for their chronic degenerative valvular disease as a result of left-sided congestive heart failure. Treatment is necessary to resolve or improve clinical signs, slow disease progression, improve quality of life, and decrease mortality. Many dogs with stage C chronic degenerative valvular disease do not live for more than 1 year after their first episode of congestive heart failure. However, there is wide variation in prognosis for individual dogs, with some dying within a few days and others living several years after diagnosis.

Defining Congestive Heart Failure:

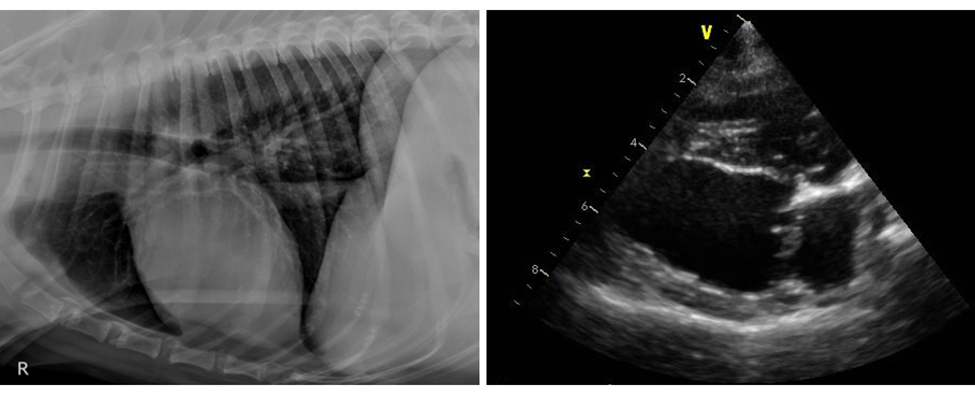

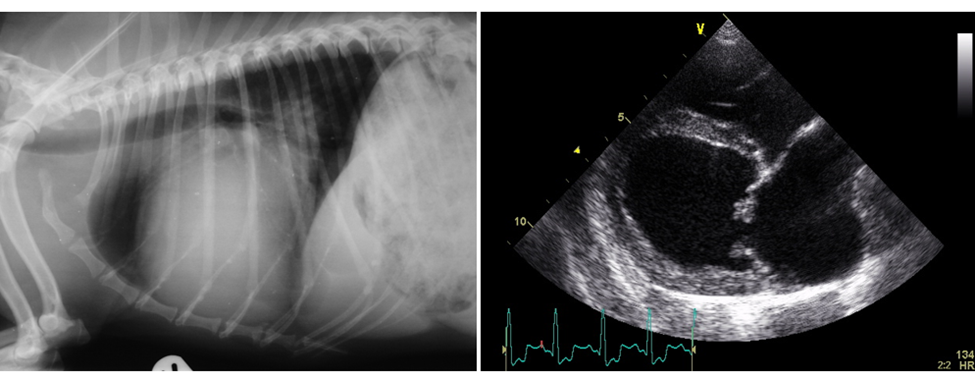

Stage C disease refers to dogs that have developed heart failure. . There are various definitions for heart failure in human and veterinary medical literature, but the common tenet of all definitions is a clinical syndrome of symptoms and signs due to cardiac dysfunction. Probably the biggest challenge with heart failure is defining when a dog has this clinical syndrome. Left-sided congestive heart failure is the most common manifestation in dogs. Diagnosis relies on a combination of clinical findings and diagnostic tests. These include clinical signs, physical examination, radiography, echocardiography and, in certain cases, electrocardiography and laboratory test results.

Diagnosing Congestive Heart Failure:

A reliable congestive heart failure diagnosis does not always require every single clinical finding to be present and every diagnostic test to be undertaken. However, the most important consideration in diagnosing congestive heart failure is recognizing that diagnosis is based on clinical judgement and there is no single reliable test to diagnose congestive heart failure. To this end, having as much pertinent information as possible will result in a more accurate diagnosis. A mistake in diagnosing congestive heart failure is relying in a single diagnostic test to make the diagnosis. A common example of this is thoracic radiographs.

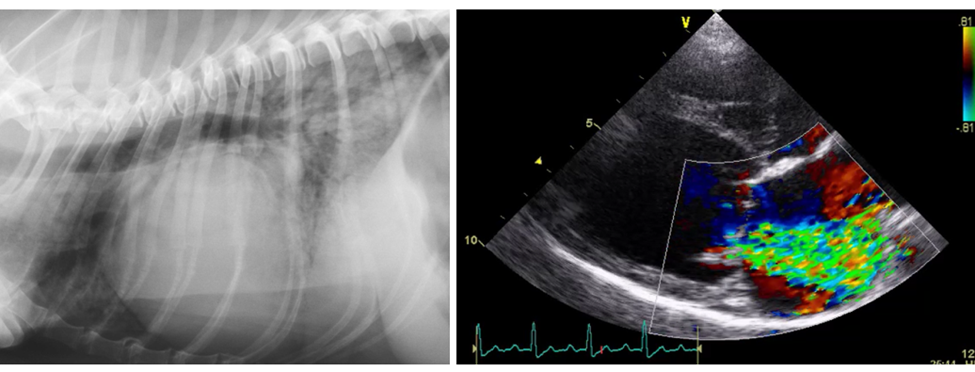

Thoracic Radiographs:

Thoracic radiographs are probably the most useful single test for the diagnosis of left-sided congestive heart failure. However, they are not always accurate. The biggest limitations of thoracic radiographs are:

1. The overlap between lung patterns for mild congestive heart failure, age-related changes, and variants of normal,

2. The difficulty visualizing lung patterns for mild congestive heart failure in poor quality radiographs (e.g. inappropriate exposure, expiratory phase of breathing),

3. The difficulty visualizing lung patterns for mild congestive heart failure when they are superimposed over soft tissue structures (e.g. cardiac silhouette, liver),

4. The time-lag between increased pulmonary capillary wedge pressure and radiologic manifestations of pulmonary edema,

5. Interpretation of thoracic radiographs is subjective and operator dependent.

The subjectivity of interpretation of thoracic radiographs is well described in human medicine. Similarly, in dogs with chronic degenerative valvular disease, a study has shown that, when blinded to the clinical information, the interpretations of board-certified radiologists as to whether left-sided congestive heart failure is present, varies significantly (9). In that study, Cohen’s Kappa Statistic was used to quantify agreement between radiologists. For this statistic, a value of 0 represent agreement equivalent to chance and a value of 1 represents perfect agreement. The agreement between board-certified radiologists in that study varied from 0.2 to 0.8, representing agreement that in some cases was substantial, but in others was poor to fair.

With the limitations of thoracic radiography in mind, it is important to not rely on radiographic interpretation alone to give the definitive answer as to whether congestive heart failure is present. Furthermore, this extends even to interpretations by a board-certified radiologist. For every interpretation by one board-certified radiologist, there will be another board-certified radiologist with a different interpretation. For those cases with equivocal or conflicting findings, a valuable role of thoracic radiography is to rule out non-cardiac explanations for respiratory clinical signs. This is highlighted by a statement in international guidelines for using thoracic radiographs to diagnose heart failure in humans: “chest x-ray is of limited use in the diagnostic work-up of patients with suspected heart failure. It is probably most useful in identifying an alternative, pulmonary explanation” (10).

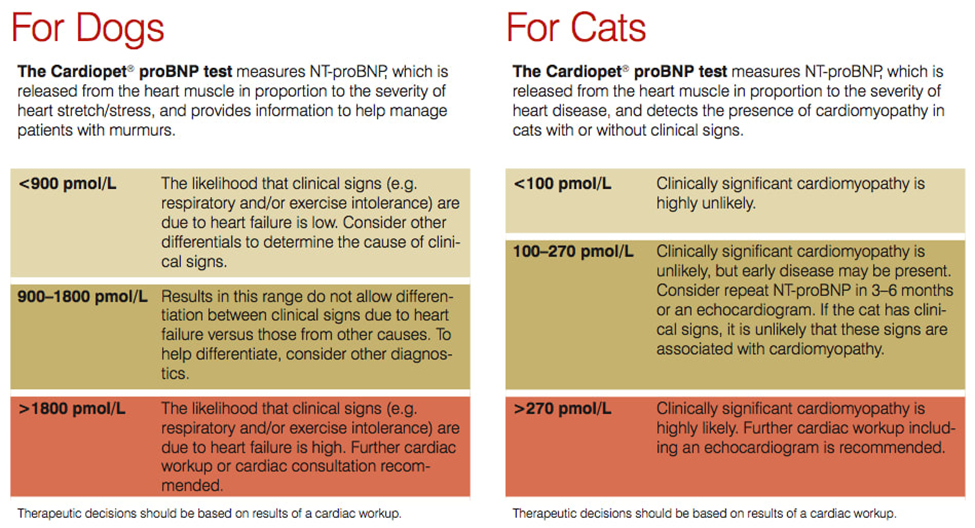

NT-proBNP:

As with thoracic radiography, NT-proBNP should not be used as a sole diagnostic tool for diagnosing left-sided congestive heart failure. However, it is a simple test with great value when used appropriately. In a multicentered study, an NT-proBNP concentration of >1,800 pmol/L was found in more than 90% of dogs with chronic degenerative valvular disease that had respiratory signs due to congestive heart failure (11). All dogs were diagnosed by a combination of physical examination, echocardiography and thoracic radiography. However, such high diagnostic accuracy can only be replicated in the real world of veterinary practice when NT-proBNP is measured in dogs with 1. respiratory signs, and 2. confirmed chronic degenerative valvular disease (i.e. by echocardiography). When measured in a different population of dogs, the accuracy falls significantly. For example, when NT-proBNP is measured in dogs without respiratory signs, a concentration of >1,800 pmol/L occurs in approximately as many dogs without congestive heart failure as with congestive heart failure, i.e. the accuracy may be no better than flipping a coin. Other limitations of NT-proBNP are the presence of concurrent disease that can result in false elevations, such as azotemia, systemic hypertension, and pulmonary hypertension. Ultimately, NT-proBNP concentration is a simple and useful test for diagnosing congestive heart failure in dogs but only when used in dogs with known chronic degenerative valvular disease and current respiratory signs. I recommend that it is used as an adjunctive test to chest x-rays for dogs that have respiratory signs and a grade 3/6 or louder, left-sided, systolic heart murmur.

Echocardiography:

In the hands of an experienced board-certified veterinary cardiologist, echocardiography is a powerful and accurate tool for diagnosing stage C chronic degenerative valvular disease. Not only is it the only test that can definitively diagnose chronic degenerative valvular disease of any stage, it can also determine whether disease is sufficiently severe that congestive heart failure is unlikely, probable or highly likely. Echocardiographic findings that are consistent with left-sided congestive heart failure are moderate or severe mitral regurgitation, moderate or severe left heart enlargement, moderate or severe elevations in Doppler estimates of left ventricular filling pressure, and evidence of pulmonary hypertension.

Guidelines for Diagnosing Congestive Heart Failure:

To accurately diagnose left-sided congestive heart failure in a dog with chronic degenerative valvular disease, I recommend the following guidelines:

- There is no single reliable test to diagnose congestive heart failure. Diagnosis is based on the clinical judgement of the doctor seeing the patient.

- There are usually compatible clinical signs (one or more of coughing, tachypnea, dyspnea, lethargy, exercise intolerance, weakness, fainting, decreased appetite).

- There is usually a left-sided systolic heart murmur of grade 3/6 or louder.

- Abnormalities of lung auscultation may or may not be present.

- Thoracic radiographs are an excellent diagnostic tool but are not definitive. The interpretation of a thoracic radiograph for the presence or absence of congestive heart failure should be made in the context of the clinical signs and physical examination findings.

- If thoracic radiographs are inconclusive, an NT-proBNP concentration of >1,800 pmol/L is supportive of congestive heart failure, but only if respiratory clinical signs and a left-sided systolic heart murmur of grade 3/6 or louder is present.

- Echocardiography by a board-certified veterinary cardiologist is recommended to determine the presence or absence of congestive heart failure in dogs that do not have a definitive answer from history, physical examination, and thoracic radiographs +/- NT-proBNP.

Ultimately, determining whether a dog with chronic degenerative valvular disease has congestive heart failure can be simple in some cases and extremely challenging in others! In cases where there is doubt or conflicting findings, consultation with a board-certified veterinary cardiologist is recommended.

Please call Main Line Veterinary Specialists on 610-947-1999 or email [email protected] if you need advice on a specific case.

Management of dogs in stage C disease will be discussed along with management of stage B disease in the next article in this blog.

Stage D:

Dogs in this stage have clinical signs of heart failure that are refractory to standard treatment. These are defined as requiring “more than a total daily dosage of 8 mg/kg of furosemide or the equivalent dosage of torsemide, administered concurrently with standard doses of the other medications thought to control the clinical signs of heart failure (eg, pimobendan, 0.25-0.3 mg/kg PO q12h, a standard dosage of approved ACEi, and 2.0 mg/kg of spironolactone daily)” (3).

Prognosis of dogs with stage D disease is generally poor, with most dogs living only a few months after entering this disease stage. Many dogs have ongoing clinical signs of congestive heart failure despite optimal treatment and/or develop comorbidities, such as azotemia, electrolyte loss, clinical signs of low cardiac output, and cardiac cachexia. Consequently, for most dogs with stage D disease, a degree of cardiac decompensation is often accepted, and the goal of treatment is to maintain an adequate quality of life with as few clinical signs as possible, rather trying to eliminate signs of congestive heart failure completely.

Management of dogs with stage D disease will be discussed in a separate article to management of stages B and C disease. This article is titled “Life After Lasix”.

References:

- Mattin MJ, Boswood A, Church DB, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors for degenerative mitral valve disease in dogs attending primary-care veterinary practices in England. J Vet Intern Med. 2015; 29(3): 847-54.

- Atkins C, Bonagura J, Ettinger S, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of canine chronic valvular heart disease. J Vet Intern Med. 2009; 23: 1142-1150.

- Keene BW, Atkins CS, Bonagura JD, et al. ACVIM consensus guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of myxomatous mitral valve disease in dogs. J Vet Intern Med. 2019; 33: 1127-1140.

- Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HFSA focused update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on clinical practice guidelines and the Heart Failure Society of America. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017; 70:776-803.

- Vitt JP, Gordon S, Fries RC, et al. Utility of VHS to predict echocardiographic epic trial inclusion criteria in dogs with myxomatous mitral valve disease: a retrospective multicentre study. Research Communications of the 27th ECVIM-CA Congress, Intercontinental, Saint Julian’s, Malta, 14th to 16th September 2017. J Vet Intern Med. 2018; 32: 525-609.

- Poad MH, Manzi TJ, Oyama MA, Gelzer AR. Utility of radiographic measurements to predict echocardiographic left heart enlargement in dogs with preclinical myxomatous mitral valve disease. J Vet Intern Med. 2020; 34: 1728–1733.

- Mikawa S, Nagakawa M, Ogi H, et al. Use of vertebral left atrial size for staging of dogs with myxomatous valve disease. J Vet Cardiol. 2020; 30: 92-99.

- Boswood A, Häggström J, Gordon SG, et al. Effect of Pimobendan in Dogs with Preclinical Myxomatous Mitral Valve Disease and Cardiomegaly: The EPIC Study-A Randomized Clinical Trial. J Vet Intern Med. 2016; 30(6): 1765-79.

- Hansson K, Häggström J, Kvart C, Lord P. Reader performance in radiographic diagnosis of signs of mitral regurgitation in cavalier King Charles spaniels. J Small Anim Prac. 2009; 50(S1): 44-53.

- Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: The Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. 2016; 37: 2129-2200.

- Oyama MA, Rush JE, Rozanski EA, et al. Assessment of serum N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide concentration for differentiation of congestive heart failure from primary respiratory tract disease as the cause of respiratory signs in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2009; 235: 1319-1325.

Come See Us

81 Lancaster Ave,

Devon, PA 19333