Updates on Treating Congestive Heart Failure, Part 3: Which Treatments to Give and When to Start Them

Dr. Simon Dennis

BVetMed, MVM, DECVIM (Cardiology)

This article is a follow-up to Updates on Treating Congestive Heart Failure, Part 2: Guidelines for Diagnosing Congestive Heart Failure in Dogs with Chronic Degenerative Valvular Disease. In this article, I will discuss treatment of dogs with ACVIM stages B and C disease, starting with pathophysiology of the disease, the rationale for treatment, and a summary the evidence supporting specific treatments at each stage of disease. Please note that, for this article, I will refer to chronic degenerative valvular disease as myxomatous mitral valve disease. As mentioned in the previous article, these names are synonymous in veterinary cardiology.

Pathophysiology

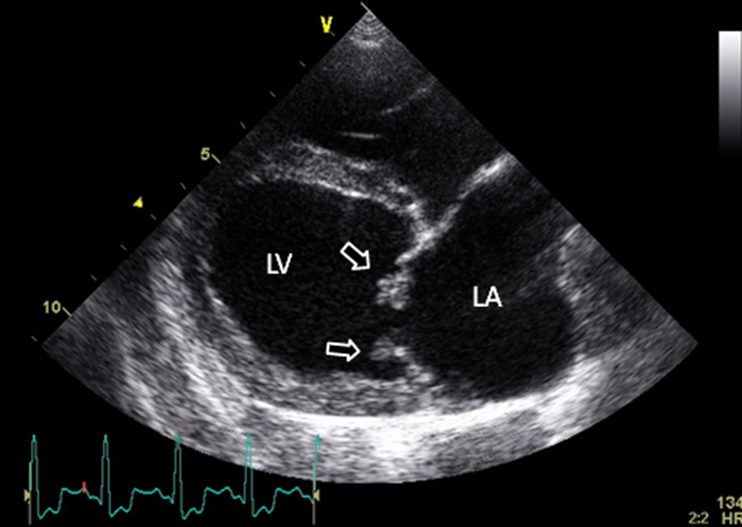

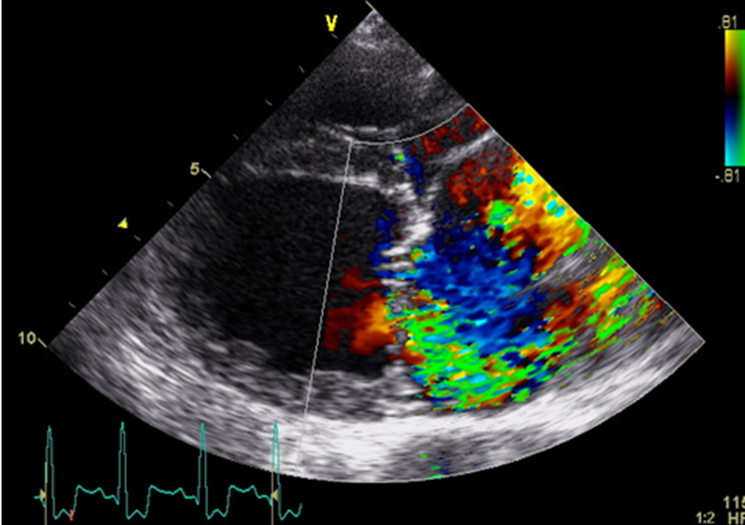

When the heart beats, a normal mitral valve allows blood to flow from the lungs, via the left atrium, to the body, via the left ventricle. In a dog with myxomatous mitral valve disease and mitral regurgitation, proliferation of the spongiform layer of the mitral valve and chordae tendineae (myxomatous change), result in thickening and weakening of the valves and tendons, valve redundancy and prolapse, and ultimately regurgitation with blood leaking backwards from the left ventricle to the left atrium (Figures 1A & 1B). The precise cause for the development of regurgitation differs for each patient. A combination of thickened leaflet edges and chordae tendineae rupture are probably the main causes for abnormal coaptation of mitral valve leaflets in most dogs. A dog can have myxomatous mitral valve disease without valve regurgitation. These dogs will not have a heart murmur but have the characteristic echocardiographic abnormalities of valve prolapse and/or thickening (Figure 1A). A murmur becomes audible when there is valve regurgitation of more than trivial volume.

Figure 1

Echocardiographic images

A: Top picture shows dilated left atrium and left ventricle, with arrows pointing to thickened mitral valve leaflets.

B: Bottom picture shows severe mitral regurgitation with color flow mapping Doppler.

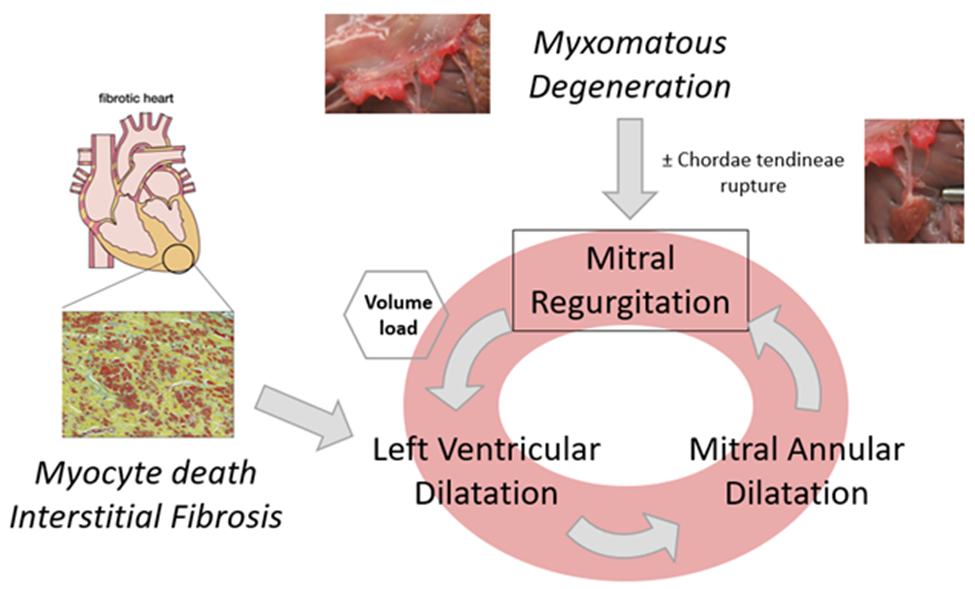

Mitral regurgitation causes a left-sided systolic murmur and volume loading of the left atrium and left ventricle. The degree of volume loading and left heart enlargement is directly proportional to the severity of regurgitation. Dogs with small volumes of mitral regurgitation may not have any discernible left heart enlargement. Dogs with larger volumes of mitral regurgitation develop left heart enlargement. This is a compensatory process. Left ventricular enlargement allows the left heart to continue to generate sufficient cardiac output to maintain normal perfusion to the body despite significant mitral regurgitation. Without left ventricular enlargement, a dog with even moderate mitral regurgitation would develop signs of systemic arterial hypoperfusion (weakness, exercise intolerance, syncope). Left atrial enlargement allows the left atrium to accommodate the increase in volume that results from significant mitral regurgitation. Without left atrial enlargement, a dog with even moderate mitral regurgitation would develop signs of pulmonary venous overperfusion (pulmonary venous congestion, pulmonary edema, pulmonary hypertension). While left heart enlargement is compensatory and beneficial in the short-term, there is a downside. Enlargement of left ventricle and, to a lesser extent, the left atrium, causes dilatation of the mitral valve annulus, resulting in further mitral regurgitation. Furthermore, the volume load on the left ventricle results in ventricular myocardial cell death and replacement with collagen (myocyte death and interstitial fibrosis), which also potentiates further left ventricular enlargement. These abnormalities have been described as “mitral regurgitation begets mitral regurgitation” (Figure 2). These processes are both causes for progression of myxomatous mitral valve disease and potential therapeutic targets for the disease. Ultimately, there is a limit to the ability of the left atrium and left ventricle to enlarge. This is reached in dogs with very severe mitral regurgitation, resulting in volume overload of the left heart and/or reduced cardiac output, and in some dogs, arrhythmias and/or pulmonary hypertension. These manifest as the classic clinical signs of heart failure in dogs with myxomatous mitral valve disease: coughing, breathing difficulties, lethargy, exercise intolerance, weakness, syncope, and decreased appetite. Without treatment, progression is inevitable, eventually resulting in death.

Figure 2

“Mitral regurgitation begets mitral regurgitation”

Treatment of ACVIM Stages B and C myxomatous mitral valve disease

The ACVIM consensus guidelines for staging myxomatous mitral valve disease in dogs (1) were described in detail in the previous article in this series. The stages of disease are A, B, C and D. Stage A refers to dogs with a known predisposition to myxomatous mitral valve disease but no identifiable structural heart disease. Consequently, treatment is not considered, or currently possible, for this stage.

Stage B disease

Dogs in this stage have identifiable structural abnormalities of myxomatous mitral valve disease (i.e. characteristic structural valve abnormalities, mitral regurgitation), but have never developed clinical signs as a result of heart failure. Most dogs with stage B disease have a heart murmur of mitral regurgitation and are asymptomatic for their heart disease. This stage is divided into 2 clinically meaningful substages:

Stage B1 disease

This describes stage B disease with no, or minimal, evidence of cardiac remodeling (left atrial and left ventricular enlargement) in response to their mitral regurgitation. Dogs with stage B1 disease have not been shown to benefit from any treatment.

Management of Stage B1 disease

Dogs with stage B1 myxomatous mitral valve disease do not require treatment. No medical therapies have been shown to be effective for delaying the progression of stage B1 disease (1, 2). Monitoring of dogs in this stage of the disease with thoracic radiography or echocardiography every 6-12 months is recommended to assess for the development of left heart enlargement or heart failure.

Stage B2 disease

This describes stage B disease with evidence of cardiac remodeling (left atrial and left ventricular enlargement) in response to their mitral regurgitation. These dogs typically have more severe mitral regurgitation than those with stage B1 disease.

Management of Stage B2 disease

The EPIC study (3), which was published in 2016, investigated the possible benefit for Pimobendan (Vetmedin®), to delay the onset of heart failure and death in dogs with myxomatous mitral valve disease and both left atrial and left ventricular enlargement. This randomized controlled trial recruited 360 dogs from 36 centers across 15 countries, making it the largest clinical trial in veterinary cardiology at that time. It showed a convincing benefit for Pimobendan to delay the onset of heart failure and death in dogs myxomatous mitral valve disease and left heart enlargement. The benefit was a 60 % prolongation of the time to heart failure or death, equating to an average prolongation of 15 months. All dogs underwent echocardiography and thoracic radiography to confirm enlargement of both the left atrium and left ventricle. The results were so compelling that the inclusion criteria for left atrial and left ventricular enlargement were subsequently adopted by the ACVIM consensus guidelines for defining stage B2 disease (1). Furthermore, the study showed Pimobendan to be safe and well tolerated. The frequency of adverse events in the Pimobendan group was no different to the frequency in the placebo group. Pimobendan (Vetmedin®) is the only medication that has been shown to delay onset of congestive heart failure in dogs with myxomatous mitral valve disease. In theory, both ACE inhibitors (Enalapril, Benazepril) and mineralocorticoid-receptor antagonists (Spironolactone) have beneficial effects in dogs with myxomatous mitral valve disease that might be expected to delay disease progression. ACE inhibitors by inhibit production of angiotensin II and aldosterone, and Spironolactone blocks the binding of aldosterone to receptors on the heart. Both angiotensin II and aldosterone are known mediators for myocyte death and interstitial fibrosis that leads to cardiac remodeling with left atrial and left ventricular enlargement, potentiating disease progression (see “mitral regurgitation begets mitral regurgitation”). Supporting this, both left atrial and left ventricular enlargement have been shown to be independent risk factors for the development of heart failure (3) and death (4) in dogs with myxomatous mitral valve disease. After encouraging results from clinical trials in humans with heart disease, the ACE inhibitor, Enalapril, has been investigated for its possible benefit to delay progression of myxomatous mitral valve disease. Two large clinical trials have been published (2, 5). Both found that Enalapril was not effective to delay the onset of congestive heart failure. However, treatment with ACE inhibitors does not always prevent aldosterone production. This phenomenon of “Aldosterone Breakthrough” has been found to occur in dogs receiving either Enalapril (6) or Benazepril (7). Perhaps a benefit is only seen when an ACE inhibitor is given in combination with Spironolactone. This was the hypothesis of a large, randomized, controlled, clinical trial published in 2020 (8). In this prospective study involving 184 dogs with myxomatous mitral valve disease and left heart enlargement, administration of both Benazepril and Spironolactone resulted in a significant decrease in left atrial and left ventricular size, echocardiographic markers of left atrial pressure, and concentrations of NT-proBNP (a marker of left ventricular and left atrial wall stress). This provides strong evidence that both Benazepril and Spironolactone inhibit cardiac remodeling. Interestingly, despite these benefits, there was no beneficial effect of Benazepril and Spironolactone to delay onset of heart failure. Furthermore, the benefits on cardiac remodeling were only observed after at least 6 months, and in some cases 12 months, of treatment. Finally, as with Pimobendan, the combination of Benazepril and Spironolactone was safe and well tolerated, with the frequency of adverse events in the dogs receiving Benazepril and Spironolactone being no different to the frequency of adverse events in the dogs receiving a placebo. The raises an interesting dilemma for cardiologists as to whether to start Benazepril and Spironolactone in dogs with stage B2 disease. There are genuine benefits that should lead to a better prognosis, no harm, but no actual evidence to delay onset of heart failure. For now, while there is consensus among cardiologists for starting Pimobendan in stage B2 disease, there is no consensus as to whether to also start an ACE inhibitor, such as Benazepril, or Spironolactone. There is consensus not to start a beta-blocker in dogs with stage B disease. This is based on the results of a randomized, controlled trial that evaluated the beta-blocker, Bisoprolol, in dogs with stage B myxomatous mitral valve disease (9). This prospective clinical trial involved 350 dogs and found no significant difference in the estimated mean time-to-heart failure between treatment with the beta-blocker and a placebo. No other medical therapies or supplements have been shown to have a clinical beneficial for stage B myxomatous mitral valve disease in dogs.

Stage C disease

Dogs in this stage have current or past clinical signs of heart failure. Affected dogs are typically symptomatic for their myxomatous mitral valve disease as a result of left-sided congestive heart failure. Treatment is necessary to resolve or improve clinical signs, slow disease progression, improve quality of life, and decrease mortality. Most dogs with stage C myxomatous mitral valve disease do not survive for more than 1 year after their first episode of congestive heart failure. However, there is wide variation in prognosis for individual dogs, with some dying within a few days and others living several years after diagnosis.

Management of Stage C disease

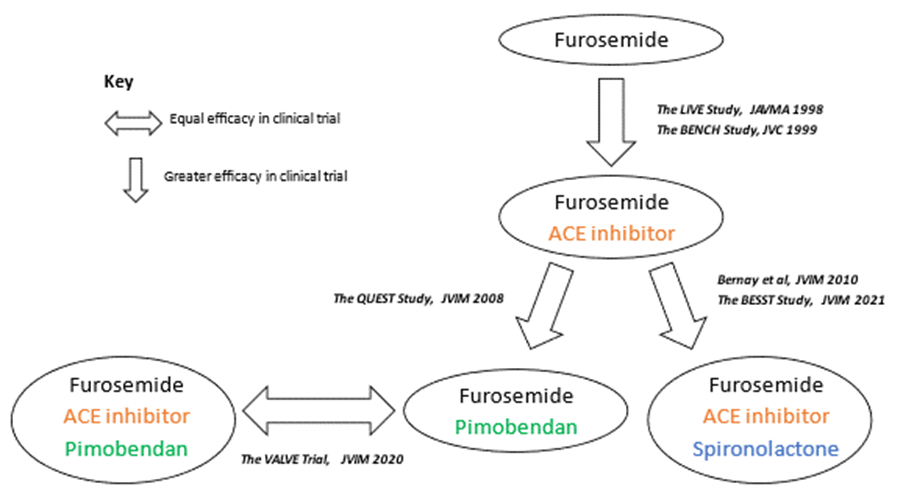

It is widely accepted that the loop diuretic, Furosemide (Lasix, Salix), is the most effective therapy for left-sided congestive heart failure from myxomatous mitral valve disease. In dogs with mild pulmonary edema and associated clinical signs, oral Furosemide at a dose of 1-2 mg/kg once to twice daily is effective. For dogs with severe edema and associated clinical signs, such as respiratory distress, Furosemide may need to be given by serial injections or continuous rate infusion, and additional therapies, such as supplemental Oxygen, may be required. In addition to Furosemide, clinical trials have identified three classes of medications that result in clinical improvement and increase in length and quality of life in dogs with stage C myxomatous mitral valve disease. These are the novel inodilator, Pimobendan (Vetmedin®) (4), the ACE inhibitors, Enalapril (10) and Benazepril (11), and Spironolactone (12, 13).

Combinations of these 4 medications have been investigated. The results are summarized in figure 3, and below:

- The combination of Furosemide and Pimobendan has been shown to be more effective than the combination of Furosemide and the ACE inhibitor, Benazepril, for treating heart failure in dogs with myxomatous mitral valve disease (4).

- The combination of Furosemide and Pimobendan has been shown to be just as effective as the combination of Furosemide, Pimobendan, and the ACE inhibitor, Ramipril, for treating heart failure in dogs with myxomatous mitral valve disease (14).

- The combination of Furosemide, an ACE inhibitor and Spironolactone has been shown to be more effective than the combination of Furosemide and an ACE inhibitor (12, 13).

Combining this information, it can be seen that Pimobendan is more effective than an ACE inhibitor, when given with Furosemide to treat stage C myxomatous mitral valve disease, and the combination of an ACE inhibitor and Spironolactone is more effective than an ACE inhibitor alone, when given with Furosemide to treat stage C myxomatous mitral valve disease. Extrapolating this information, I recommend administering the combination of Furosemide, Pimobendan, an ACE inhibitor, and Spironolactone, whenever possible, for optimal management of stage C myxomatous mitral valve disease.

Figure 3

A summary of clinical trial results comparing different medications combinations for treating stage C myxomatous mitral valve disease

Additional treatments for stage C disease include Diltiazem and/or Digoxin for dogs with persistent atrial tachyarrhythmias, such as atrial fibrillation, Sotalol for dogs with significant ventricular arrhythmias, and Sildenafil for dogs with moderate or severe pulmonary hypertension that is disproportionate to the severity of left heart disease, in combination with either right-sided congestive heart failure or clinical signs of poor cardiac output (syncope, weakness) (1). Furthermore, since an increase in afterload can increase severity of mitral regurgitation, a dog with stage C myxomatous mitral valve disease that has systemic hypertension or chronic high-normal systolic arterial pressure may benefit from blood pressure lowering treatment. The preferred medications are the arteriodilators, Amlodipine or Hydralazine.

Management of dogs with stage D disease will be discussed in a separate article to management of stages B and C disease. This article is titled “Life After Lasix”.

If you have a cardiology case that you wish to refer to Main Line Veterinary Specialists, please contact us below:

REFERRAL FORM FOR VETERINARIANS

SCHEDULE AN APPOINTMENT FOR YOUR PET

References:

- Keene BW, Atkins CS, Bonagura JD, et al. ACVIM consensus guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of myxomatous mitral valve disease in dogs. J Vet Intern Med. 2019; 33: 1127-1140.

- Kvart C, Häggström J, Pedersen HD, et al. Efficacy of enalapril for prevention of congestive heart failure in dogs with myxomatous valve disease and asymptomatic mitral regurgitation. J Vet Intern Med. 2002; 16(1): 80-88.

- Boswood A, Häggström J, Gordon SG, et al. Effect of Pimobendan in Dogs with Preclinical Myxomatous Mitral Valve Disease and Cardiomegaly: The EPIC Study-A Randomized Clinical Trial. J Vet Intern Med. 2016; 30(6): 1765-1779.

- Häggström J, Boswood A, O’Grady M, et al. Effect of pimobendan or benazepril hydrochloride on survival times in dogs with congestive heart failure caused by naturally occurring myxomatous mitral valve disease: the QUEST study. J Vet Intern Med. 2008; 22(5): 1124-1135.

- Atkins CE, Keene BW, Brown WA, et al. Results of the veterinary enalapril trial to prove reduction in onset of heart failure in dogs chronically treated with enalapril alone for compensated, naturally occurring mitral valve insufficiency. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2007; 231(7): 1061-1069.

- Lantis AC, Ames MK, Werre S, et al. The effect of enalapril on furosemide-activated renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system in healthy dogs. J Vet Pharmacol Ther 2015; 38(5), 513-517.

- Lantis AC, Ames MK, Atkins CE, et al. Aldosterone breakthrough with benazepril in furosemide-activated renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system in normal dogs. J Vet Pharmacol Ther 2015; 38(1), 65-73.

- Borgarelli M, Ferasin L, Lamb K, et al. DELay of Appearance of sYmptoms of Canine Degenerative Mitral Valve Disease Treated with Spironolactone and Benazepril: the DELAY Study. J Vet Cardiol. 2020; 27, 34-53.

- Keene BW, Fox PR, Hamlin RL, Beddies GF, Keene TJ, Settje T, Treml LS for the HECTOR investigators, Keefe TJ. Efficacy of BAY 41-9202 (Bisoprolol Oral Solution) for the Treatment of Chronic Valvular Heart Disease (CVHD) in Dogs [Abstract]. Presented at the 2012 ACVIM Forum, June 1, 2012, New Orleans LA.

- Ettinger SJ, Benitz AM, Ericsson GF, et al. Effects of enalapril maleate on survival of dogs with naturally acquired heart failure. The Long-Term Investigation of Veterinary Enalapril (LIVE) Study Group. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1998; 213: 1573-1577.

- BENCH (BENazepril in Canine Heart disease) Study Group. The effect of benazepril on survival times and clinical signs of dogs with congestive heart failure: results of a multicenter, prospective, randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, long-term clinical trial. J Vet Cardiol. 1999; 1: 7-18.

- Bernay F, Bland JM, Häggström J, et al. Efficacy of spironolactone on survival in dogs with naturally occurring mitral regurgitation caused by myxomatous mitral valve disease. J Vet Intern Med. 2010; 24(2): 331-341.

- Coffman M, Guillot E, Blondel T, et al. Clinical efficacy of a benazepril and spironolactone combination in dogs with congestive heart failure due to myxomatous mitral valve disease: The BEnazepril Spironolactone STudy (BESST). J Vet Intern Med. 2021; 35(4): 1673-1687.

- Wess G, Kresken J-G, Wendt R, et al. Efficacy of adding ramipril (VAsotop) to the combination of furosemide (Lasix) and pimobendan (VEtmedin) in dogs with mitral valve degeneration: The VALVE trial. J Vet Intern Med. 2020; 34: 2232–2241.

Come See Us

81 Lancaster Ave,

Devon, PA 19333